Almost everybody has heard something about a seal called a “fur seal”. Some people have only vague image of this animal, other watched TV programs about life of seals, and for some of us fur seal is a site of special scientific interest.

For the most of the year northern fur seals wander the vast of the Pacific Ocean. About seven months they keep deep offshore. As a result of evolution they had adapted to water life well enough. Their smooth streamlined body in covered by warm, waterproof, strong fur. Instead of legs they have leathery flippers. Even their ears are small, fit flush to the head tubes which do not hinder sliding in water.

The Ocean is the element of the northern fur seals. They are masterful swimmers and divers, and can even sleep on water. During play seals leap out of the water the same as dolphins.

Fur seals hunt and feed only in water.

Although they spend most of their life in water, they real home is a land, where fur seals are born, take first breath, and nurture.

At the end of spring after winter migration northern fur seals get out from the water at coasts of small islands. During all warm season seals live ashore returning into water only to feed.

Classification and origin

The same as all animals nurturing their babies with milk, northern fur seals belong to a class of mammals (mammalia).

Whole winter, most part of spring and autumn they spend in water. Such pelagic life is possibly only with limbs adapted for swimming. Hands and feet of fur seals were modified into flippers suitable for swimming and maneuvering in water. That is why the order to which walruses and all seals belong is called pinnipedia order. at the sides of the head northern fur seals have small ears in form of turned back tubes. only members of pinnipedia otariidae family possess such ears.

Genus and species are northern fur seal (callorhinus ursinus), originate from greek and latin and means “bear-like”. young seals and female with their brownish fur really resemble bears.

Northern fur seals inhabit mainly the North Pacific. Several species of seals also live in the southern hemisphere and belong to southern fur seals (Arcto¬cephalus).

Eared seals including the northern fur seal descended from ancient ancestors Enaliarctus mealsi, resembling the otter and loved 24¬25 mln. years ago. They had flippers and were good swimmers. The form of their skull suggests that they could dive for a long time while hunting. The center of all eared seals family members’ dispersal is the Pacific Ocean.

Distribution and migration

The northern fur seal inhabits northern island of the Pacific Ocean.

During ice-free season from May to November the land population of fur seas is mainly concentrated for breeding on rookeries in several areas. The most draw together on the Pribilof Islands (several hundred thousands), a little less – on the Komandorskie Islands (about 1,5-2 hundred thousands) and the Tuyleny island in the Sea of Okhotsk (about hundred thousands). Small colonies of the north fur seals breed on some of the Kuril Islands and on the San Miguel Island near California. The north fur seal population currently is between 1 – 1,5 mln. seals.

The fur of the north fur seals is very string and warm that has caused mass extermination of seals in the 19th and 20th centuries. The other problem of seals is helplessness on rookeries as the pod of thousands cannot escape fast in water in case of any danger.

One of the reasons that seals choose small hard-accessible islands for rookeries is absence of big predators there which could hunt seals assailable on land. Predators could also break well-functioning structure of rookery, i.e. natural reproduction.

The number of the north fur seals’ rookeries on the Komandorskie and Kuril Islands was larger up to the 19th century. The intensive seal hunting at that time almost destroyed the population of these animals. Some rookeries were recovered due to conservation measures, prohibition of commercial hunting and preservation from poaching. But some rookeries are still empty.

In September-October adult and young seals leave rookeries and swim to the Sea of Japan or on the Californian coast in small groups or individually. Some part of seal’s population dissipates in the Pacific Ocean. They all take a rest and intensely feed at shallow water areas

Habitat

In warm period seals come out on small and average islands far from the continent. They choose for some unknown reason sand or rocky beaches with flat ramp at shallow water and large puddles renewed by sea tides where seal-babies may learn to swim in safety.

Since old times, rookeries chosen by large pods of thousands had become permanent. Every year after winter travel seals return to the same rookery and even the same part of the coast where they were born. But savage extermination of rookery’s dwellers resulted to the full decay of the rookery. Many of rookeries destroyed in the 19th century are still empty. But due to prohibition of commercial hunting, population of seals has slowly increased. Some of devastated rookeries were repopulated by the settlers from other areas.

What is most remarkable is that new seal rookeries appeared after complete wasteness at the areas where they existed hundred years ago.

Appearance, form of limbs, movement

Northern fur seal – is a big animal with smooth and streamlined body of a perfect swimmer. Its fur is smooth and shiny black-brown in water. When a seal comes out of water on shore, gives itself a shake and dries, the fur becomes solid and fuzzed. The color of adult males varies from dark-brown, almost black to reddish-brown or sand-colored. Old seals may have streak of gray. The pride of an adult male is heavy and strong neck with harsh fur passing into nightly chest. There is a heavy fat layer under thick skin of neck and chest.

All this “battle armor” of a seal bull is vital for him. They protect a male in fights with competitors while territory carving-up during breeding season.

The northern fur seals have a very small tail of no practical importance.

An adult north fur seal male is much larger than female. Male may weigh more than 200 kg that is 4-5 times more than females’ weight of 50-60 kg (the difference between male and female is called sexual dimorphism). Big size and power give a priority in competitive fighting for a place at rookery. Big male is also visible from far. A competitor sees a “resident” even from the water approaching to the rookery and he may hesitate to demonstrate aggression.

Seals’ females are smaller than males, have brown fur and streamlined body. The fur on the chest is lighter with silver-cream tint. Often lighter fur flows to the neck, and even whole lower part of body may be silver-gray. This coloring is a good camouflage making a seal hidden against a water surface and, thus, protecting it from a predator emerging from the depth

Young 2-3-year old males are similar to females in size, body form and color.

New-born seals weigh 3-5 kg and have black less fluff fur till the first moult than adults.

The foreflippers are large and long looking like wings. The flippers skeleton has all the major skeletal elements of the forelimbs of land mammals, but modified as a result of life in water. Foreflipper has cartilage endings of digits and is webbed. When moving in water, a seal seems to fly, flapping by forelimbs as if wings. Seals can swim up to 15-17 km/h in case of danger, but generally they cruise at 9-11 km/h speed.

Hind limbs of a northern fur seal are also webbed. They function as rudders and balancers for swimming and diving.

The northern fur seals can dive to depths more than 200 m. However, they ordinary don’t dive such depths and prefer to stay in surface layer 10 to 20 m thick.

The hind flippers have claws at the end of each digit for fur combing and cleaning. In order to scratch, a seal rises and flexes hind flipper, web bends, and claws are ready for scratching.

When on land, a seal moves clumsy leaning on the folded flippers. They can run very quickly for short distances by moving pairs of hind and foreflippers in turns.

When a seal rests on shore, it combs its wet fur with hind flipper claws or chafes itself by foreflipper in order to cover its fur with thin fatty film from oil glands on “palms”.

Fur – body coat

Northern fur seal’s fur consists of thin guard hairs covering shorter and denser wavy underfur. Guard hairs are covered by the oil from glands and become wet only from outside protecting warm underfur from water. In such waterproof coat a seal can swim in cold water with impunity. Seal’s fur is also one of the strongest compared to other animals.

Seals molt each year in autumn. The old fur is gradually changed by a new one not affecting seals’ routine rhythm of life too much.

Grown up black pups shed their black fur in September. A new, light gray fluffy fur covers pups turning to the most beautiful silver (or gray) seals.

Sences and adaptation to water life

Vision

The northern fur seals spend most of their life in water and even under water, that’s why their eyes are adapted for water conditions. Seals have large eyes that provide wide field of view forward and around head. Internal structure of seal’s eye suggests binocular vision providing, however, rather acute vision.

ОThickened cornea protects seal’s eyes from salt water. Fur seals have a well-developed choroid with reflecting layer called tapetum. Tapetum reflects light passes through eye’s retina back on photocepters. The double light passage through the retina improves eyesight in poor light, for instance, while deep diving.

Fur seals have rather good eyesight on land. Experiments show that seals distinctly identify figures of different forms. At rookeries seals almost do not respond to motionless objects, but notice moving ones. For instance, bull demonstrates to other counterparts its large figure which they see and respond from far. But still in most cases seals rely on their sense of smell more than eyesight and go scenting about.

When in spring seals return to the rookery after winter travelling, the swim near the coast raising their heads high above water and scanning the beach in search of any danger. If they notice something suspicious, they rush back in waters.

Smelling and breathing

Olfactory and respiratory systems of the northern fur seals are adapted both to air and water.

Olfactory is less effective over a distance, that’s why seals rely on their eyesight before coming out of water scrutinizing each object before them. Coming on shore, a seal sniffs vigorously at the ground. It goes sniffing about. A smell of the rookery contains very important information whether the rookery is new or old, is there any other seals or predators.

According to the smell, a bull determines its territory and breeding condition of females. A female identifies its pups, place at the rookery, males, etc.

Brain morphology with well-developed olfactory divisions of the northern fur seals proves an acute sense of smell. Complex structure of nasal cavity and its soft tissues also suggests high nasal sensitivity.

Seal’s nose is well adopted for diving. There are special volume sections for incoming air quick filtering and warming in its nasal cavity. The agility in this case is very important for quick exhaling-inhaling process when a seal comes up only for few seconds to replenish air stock in lungs.

Usually seal’s nostrils are closed even during resting.

A fur seal has a short and rare exhaling-inhaling cycle compared to land animals. Respiratory pause (a time between each exhaling-inhaling) is about 5-10 seconds. Before diving, a seal exhales, makes a deep breath and close its nostrils using a special muscle. While diving, seal’s nasal cavity with its inner folds is tight compressed, that completely excludes penetration of water in respiratory passages.

A northern fur seal can stay submerged (usually during hunting) up to 10 minutes and more. Its lungs have additional lung lobes and are adapted for long breath holding. As with other marine mammals, when a harbor seal dives, its heart rate slows, and blood with muscles retain more oxygen

Hearing

The northern fur seals have a good sense of hearing both in and out water. External ear is a longitudinal skin-cartilage fold about 5 cm long. In the air a small conic ear opens by ear muscles, and a seal intercept sound the same as land animals. In water ear folds, lateral borders of external ear close keeping out water penetration. Morphologic structure of middle- and inner- ear suggests seal’s ability to perceive wide-ranging sounds including ultrasounds.

Tacktile

Tactile reception or sense of touch is very important during a rookery season. Despite the overcrowding of a rookery, seals try to avoid direct skin-to-skin contact. But in some cases they can come in contact. For instance, nursing mother allows a pup to lean on and get on its back, and also touches a pup by its neb, put its head on a baby while sleeping. Tactile reception is effected through tactile sensors of skin and special hairs – vibrissae located at the whole body. A lot of vibrissae are on seal’s face. There are about 22-23 vibrissae on the upper lip on both sides of face. Seals move their vibrissae for tactile perception while approaching to some object or to each other. Tactile sensitivity is also used by seals in water while moving to inspecting objects.

Taste

Little is known about a seal's sense of taste. But observations in zoo and dolphinariums show that fur seals distinguish food taste and also have strong preferences for specific species of fish or squid rejecting other food they’ve tasted.

Sleepeng in water and on land

In winter northern fur seals feed and rest intensively while traveling in the ocean. They also have to get enough sleep. As they spend much time at sea, they must sleep in water.

Scientists have noticed that while sleeping in water, a seal assumes specific posture – it floats on one side on the water surface submerging one foreflipper and raising other flippers put together. Flippers are put tight in order to save heat. While sleeping, a seals drags by a free foreflipper to keep its body position in water.

According to the studies, fur seals are able to sleep in water with only half their brains. The other half of the brain remains awake and alert controlling body, head and flippers position. As far as seals periodically turn over, both hemispheres get enough sleep in turns.

Respiratory pause is the same as during sleep on land, i.e. about 5-10 seconds.

On shore fur seals sleep in different postures. Most often they sleep lying on belly or sidelong, and if it’s cold, they lie huddled up and putting their bare flippers to fluffy belly.

Behaviour

Social structure

Summer, rookery and winter life of seals are absolutely different mainly in social structure.

In summer seals live on shore together with thousands of the counterparts almost shoulder to shoulder. In this crowd pups are born and brought up, bull fight for the territory, intensive and short-living mating games take place.

In winter, during water life, seals almost break all interaction and live individually or in small groups in areas of their migrations.

The first adult males – bulls come out of sea to the habitual reproductive rookeries in May. They come to the beach very carefully and with cautions smelling out attractive place.

“Residents” attitude to the new-comers is very aggressive. They fight with each other for division of the rookery into sectors for their future families called harems.

From June number of fights decreases, each bull protects its territory, and females alone or in small groups come to the rookery. They come out of the sea and settle down on the territory of some bull. Usually they choose the same places as the last year.

A bull meets females and tries to keep them on its area blocking their way. Gradually groups of females are organized around bulls. Such groups are called harems.

In time new females come, harems grow and finally merge with each other. As a result, a numerous and noisy rookery of moving, screaming and interacting northern fur seals forms.

Although seal females are lying almost back-to-back, they avoid touches with neighbors. Conflicts between females break out constantly when one of them shatters the calm of the other. If touched by another, a female seal responds with growling, snorting, roaring, and threat postures, but usually they do not come to biting.

When pups are born, relations between females become even worse. Females chase away neighboring females from their babies and another’s babies keeping them away from milk.

10 days after coming on shore, pup’s birth and copulation a fur seal female returns to the sea to forage for several days.

During this time tens and hundreds of pups gather on the separate areas serving as “playgrounds” or “kindergartens”. Pups sleep here for several days and then play with other peers waiting for mothers.

In a week mother returns on the rookery, finds its baby and nurses it with milk during a couple of days. Then mother leave a pup again to forage.

At about 30-day age pups at the first time go to the neighboring puddle or shallow water where they together with other pups adapt to cold water sitting under spindrift and combing wet fur. Later they enter water, learn to swim and dive, play with peers.

In coastal season seals also form separate bachelor colonies near the reproductive rookeries. There so-called bachelors inhabit, i.e. young males which do not participate in breeding yet. The life of bachelor colonies is full of joy and careless. Some males sleep sprawling, others spend time in fights. They fight by twos or threes, but do not bite each other seriously, only honing their skills of fight required in adult life.

In August northern fur seals start gradually molting, breeding season comes to its end. Animals take a rest, sleep, molt and gain strength after intensive summer and before winter migration. Juveniles suck mother’s milk and train hard, perfecting their swimming and diving skills. Black pups become gray (silver) after molting.

In October when the weather is turning colder, at first young northern fur seals and then adult leave the rookeries one by one or in small groups. They start their marine wandering.

Territorial behaviour and vocal sounding

After division of the territory in spring, fur seal males protect their demesnes from each other and intruders. Males identify their territory by smell even in crowd of females with pups. They regularly patrol the demesnes walking along borders and sniffing to the earth and harem females. While walking, a bull emits specific clicking sounds extraordinary high for such a big animal.

This sound is a kind of signal for the others that the area is occupied and there is an active bull ready to accept new “wives” in his harem. A bull warns all who try to encroach on its territory by well-noticeable S-shaped posture. Towering among females, a bull is well-observable for rivals.

In this posture opening its chaps wide and looking at rival’s side, a bull sounds its main signal in form of threatening roar. Vibrating bass sound is loud and similar to vessel’s siren heard far beyond the rookery and damps down rookery’s noise. Several bulls frequently roar at the same time. In such way an owner of the territory warns intruder.

If intruder still reaches the area border, an owner demonstrates its force. A bull falls on its chest, stretches out its neck and head to the rival’s side and harshly barks.

A rival respond in the same way. And if intruder does not stop, a fighting starts. They push each other chest-to-chest, try to press the enemy, bite each other’s large neck or side. The aim of the resident is to chase the intruder away from its territory. Usually the alien steps back and escapes to the sea. While it runs past other areas, their residents also chase it and bite all the way to the water.

When the rookery life is calm, bulls sleep or pay attention to females. Sometimes patrolling the boundaries, they meet with neighboring bulls and demonstrate forces, barking and roaring. But such “good-neighbourly” demonstration never runs into fighting, in this way males just proves their presence and territory occupation. On the constant rookery bulls know each other in appearance, smell and other features.

Northern fur seal females also have their microterritory on the rookery. Usually it’s a place of female on the harem area of one of the bulls. Mother shares its haul-out site with its pup and protects the place from other females’ and their pups’ invasion by means of threatening postures and sounds. As pup grows their haul-out space shifts out of harem area boundary.

Mating and maternal behavior

Vocal signals

Northern fur seal females give birth to one pup soon after arriving on the rookery and in few days they are ready to mate again.

During one day a male pays attention to a female chosen by smell.

A male approaches and nosing a female, then emits “harem call” analogous to groan and tries to hold a female beside. On the nest day a male is no more attracted by the smell of this female. A male turns its attention to the next female among its “wives”. Harem of one bull may contain up to 50 or even more females. A bull may mate with each of them.

A mother keeps a new-born pup close to itself during first 10 days before her departure to forage at sea. Mother communicates with a baby by tender, quite and thin cries. If a baby moves away from mother, she carefully carries a baby back with her teeth and then gives a pup her belly with four mammary nipples. If other seals try to approach to baby or sniff it, a mother chases them by threatening sounds and postures with open mouth.

Mother leaves a baby for a week or more to forage at sea. After returning, she has to find her own baby because usually females reject strange pups. She wriggles through other seals to her place and calls a baby with loud cries. Finally she founds the pup, usually near a place of is birth. She chases all strange pups approaching at her voice by threatening posture and sounds.

A pup also tries to find the mother by the time she returns, calling her by thin cries. They recognize each other by voice and smell. During several days mother stays with pup and nurse it with milk and then leave again for feeding. Fur seal’s milk is rich and nutritive. That’s why despite the breaks in nursing, pups grow fast. A female nurses a pup till their departure in October when pup is about 4 months old.

Feeding

Northern fur seals different kinds of fish, squid, cuttlefish, and even jelly-fish. Some kinds of fish they prefer more than others, for instance, walleye pollack, capelin, lanternfish, squids. But if the number of habitual food reduces, seals can easily change the diet to the widespread and easily-accessible fish species.

Northern fur seals hunt in large groups in relatively shallow-waters on co-called “marine banks”. There are a lot of fish and other animals in such areas. Usually fur seals eat schooling fishes near the surface and do not dive deep. To hunt squids, they dive at shallow-water. Scientists have found stones in the stomachs of seals. May be they swallow stones occasionally, together with squid’s tentacles, or for assisting in digestion and reduce of intestinal parasites, and may be these stones add extra weight for ballast while diving.

Usually northern fur seals hunt small fish and swallow it whole in water. If they catch large fish, they rise at the surface and tear it into chunks shaking their heads the same as dogs.

Northern fur seals feed and rest intensively in winter during marine migrations to ice-free waters of the Pacific Ocean. During breeding season seals and especially bulls hunt rarely. Defending their territory, males do not leave the rookery for 2-3 weeks and during this time do not eat anything.

Females leave their pups for 5-7 days for foraging at sea. During 1,5-2 days they feed babies with very rich (up to 50% fat content) milk and then go out for hunting again.

Northern fur seals’ gastric activity and food content provide intensive digesting of the food for 12-14 hours. That’s why seals recover energy very fast.

Northern fur seals never drink water. They generally obtain the water they need from their food

Longevity

Northern fur seal live quite a long time. Some species live up to 3- years and even more. 26-27-year old females still may have pups.

But the most live less. There is high pup mortality from hunger, illnesses and incidents. About 70% of young seals die in the first two years. Many pups can’t survive during their first wintering at the open sea or can’t stand switch to adult food.

Northern fur seals can be preyed upon by killer whales (Orcinus оrса) or sharks, but in general little is known about their marine life. As all wild animals seals are susceptible to different diseases among which usual surgical disorders – fractures, dislocations, eye, jaws and skin injuries. Frequently they can become entangled in fishing nets caused drowning.

Human impact

Relations between northern fur seals and human were always strained. In past people devastated seals’ rookeries for fine coats of fur seals. Nowadays seals’ coastal hunting is restricted, their rookeries are protected, and marine hunting is prohibited. Thanks to these measurements seal population remain high.

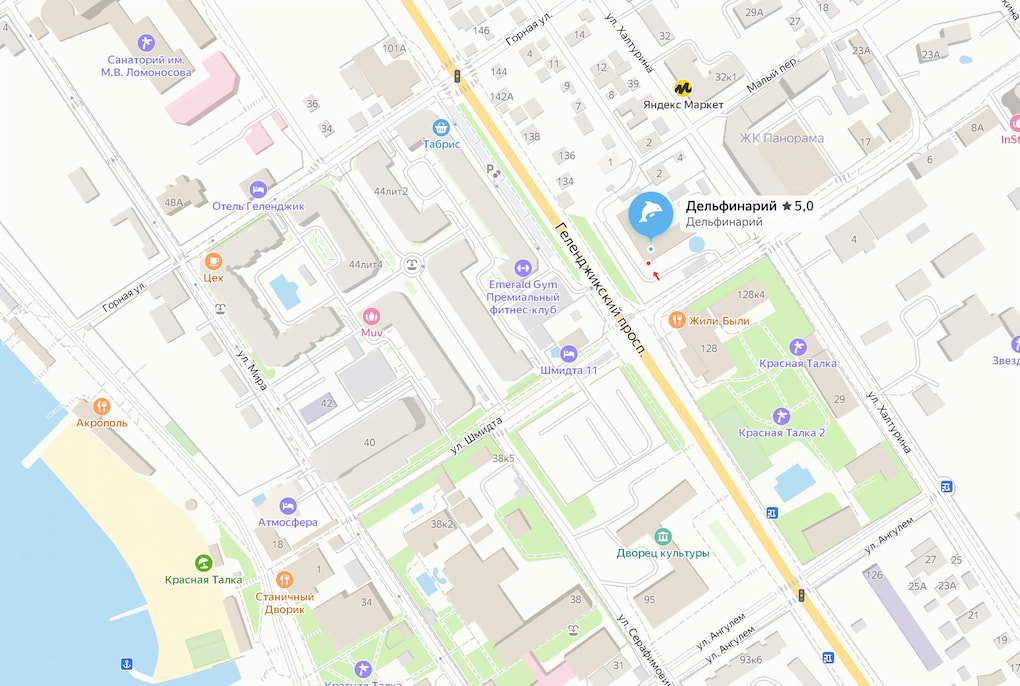

Northern fur seals are easy to keep in zoos and dolphinariums. The main is to provide an access for cool and clear water for physical exercise and to avoid overheating. Kept in captivity, seals are easy to train. These animals perfectly perform tricks and entertain visitors in dolphinariums and circuses.

Copyright belongs to T.V. Lisitsina. Any use of the text is only with consent of the author.